The Robots Are Not Your Friends

The amount of unsecured internet-connected devices that are crawling around our homes (sometimes literally) has been on the rise for years. The latest Amazon Echo hack reminds us that these devices are powerful tools that cannot, and should not, be blindly trusted on our home networks.

Introduction

So who are the robots, you may be asking? In short, 'the robots' are the automated devices we have in our homes to make things more convenient. These devices are commonly referred to as being part of the "Internet of Things," or "IoT devices," or simply just "IoT." And it's true that IoT revolution has brought us many conveniences. Roomba (or something roomba-like) cleans your floors, Wemo (or a Wemo knock-off) controls your lights, and a whole raft of kitchen doodads help you make snacks and meals and coffee exactly when, and how, you want. So what’s the problem here?

In short, the problem is that the Internet of Things is incredibly broken, and has been for a while. According to an oft-cited research study conducted by HPE in 2016, 60% of IoT devices raised security concerns- and that’s just with their user interfaces. Fast forward to last year and a Palo Alto study showed that IoT devices were 1) increasingly prevalent in homes (and, by way of work from home, on corporate networks as well), and 2) are just as insecure as ever.

Many people make the mistake of thinking that size matters. ‘Amazon is a huge company,’ they reason. ‘Surely the Echo can be trusted.’ (spoiler alert: it can not.) After all, the Echo is just another IoT device.

As a refresher, here's a list of commonly disclosed IoT security flaws that regularly make the news the news:

- Devices that are programmed in a hurry (and then never updated again)

- Devices that have default credentials (or even a secret backdoor) built into them

- Devices that disregard other modern best security practices (this includes things like credentials stored in plaintext, leaving telnet ports open, defaulting to zero encryption, etc.)

Now it's true that these problems are all from the manufacturer. Things take a turn with the Echo, because of the power we as consumers choose to give it. Namely:

- Devices that have too much control of other devices

Simply put, an Echo (or a Google Home, or an Apple HomePod, etc.) has more power. A command like “Alexa, unlock front door,” or “Alexa, order more cat food,” can cause devices to activate, credit cards to be charged, and any other number of creative conveniences. Sometimes these commands are accidentally triggered. This can go from the funny but expensive (“Alexa, order me a dollhouse”) to the disturbing (Like the time Alexa recorded a private conversation and sent it to another user).

The Alexa vs Alexa Attack

Which brings me to this most recent attack. In what researchers are calling an ‘Alexa vs. Alexa' (or AvA) attack, a bluetooth connection is made from outside the house (but within bluetooth range) and Alexa will respond to commands that issue from the Alexa device itself.

There appear to be no limitations on what the AvA can get the Alexa to do. An attacker can have it do anything it’s capable of, including manipulate smart devices (such as door locks), impersonate Alexa skills, manipulate Amazon shopping carts, call phone numbers, and delete voice recordings.

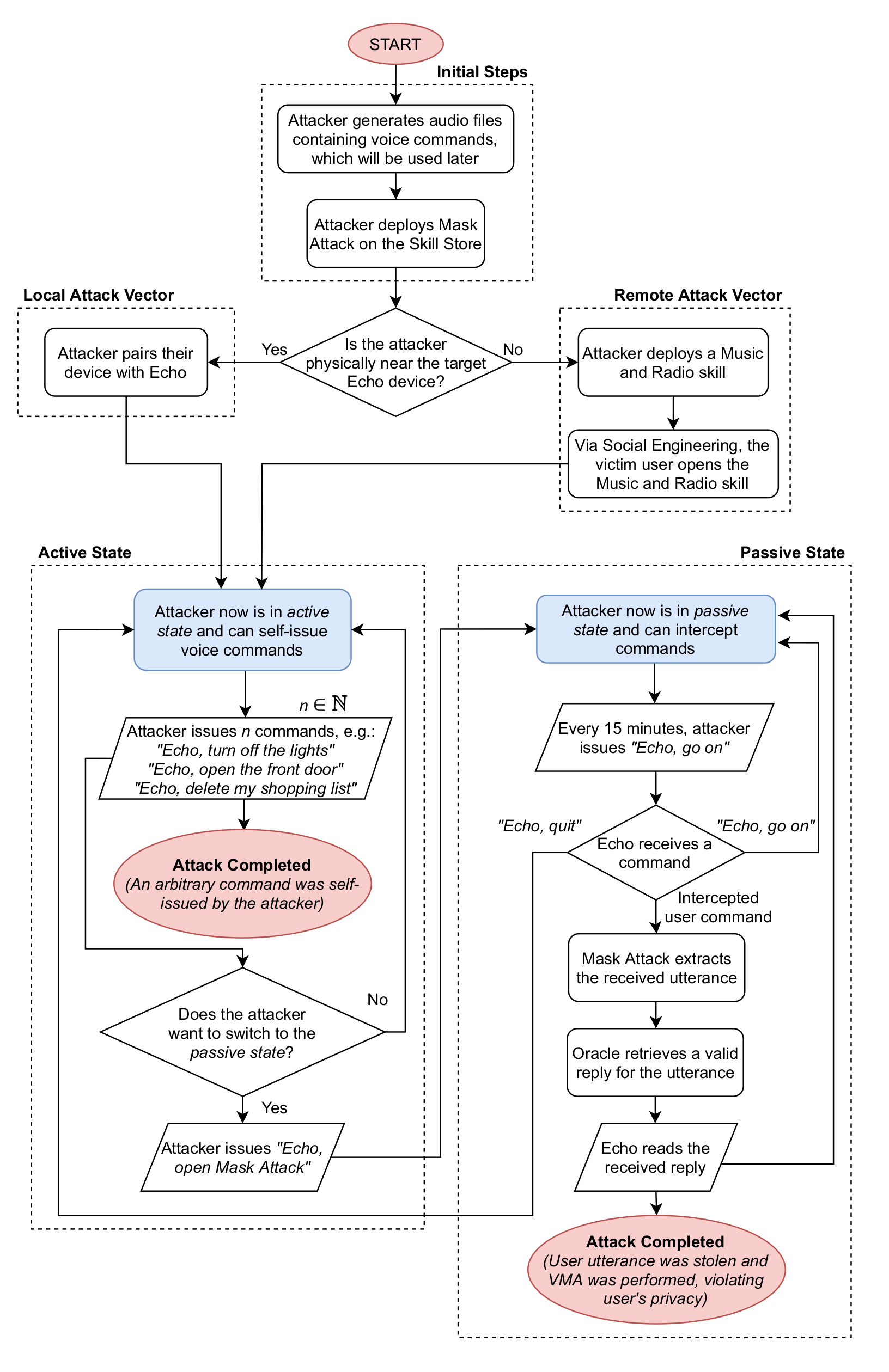

The full paper describing the attack is available here: https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.08619, and it is well worth the read. However, for brevity’s sake (bold thing for me to say 1,000 words in, I know...), I just want to highlight the provided flowchart that describes the way the attack works. I think it does a good job showing how blind trust in these IoT devices leaves us open to attack.

Flowchart describing the Alexa vs. Alexa attack through multiple mechanisms and attack states.

It’s a clever attack that takes advantage of Amazon’s bad security (allowing the speaker to take commands from itself). And, yes, Amazon could do a better job guarding the Skill store (a sisyphean job if I’ve ever heard of one- witness the Google Play store). But the AvA attack also highlights where our blind trust in these devices puts us into danger. Why do we even allow those skills to be installed? Why isn’t there a passphrase on the bluetooth connection, or on commands like ‘unlock the front door?’ In many cases the answer is the choice of convenience vs security. It’s choosing to trust the robot. But as we have seen, the robots are not your friends.

So what should you do?

The trick here is to treat IoT devices (even the “important” ones like Alexa) as the tools that they are. Assume that they are dangerous (because they are), and plan your environments around worst case scenarios based on these dangers. Be wary of the robot.

First, be vigilant about updating your devices. And, a device is brand new on the market, wait and see if it remains supported by the vendor. If it turns out that the device is not sufficiently supported (something kickstarter-based devices are notorious for) then it could be a candidate to wait on buying until you can get more information on its long-term prospects.

Second, be certain that all of your IoT devices are on a guest network. They should never share network space with your computers or smart devices, full stop. Ideally the guest network is isolated in such a way that the IoT device can access only the Internet, not other IoT devices on the guest network. This way, even if a single device is compromised, it will not provide an attack vector inside of your network.

Third, enable passcodes for all sensitive activities. This can be an activity-by-activity decision. You may decide, for example, that ‘turning the lights on’ via Alexa does not require a passcode, but ‘unlocking the front door’ (or making a purchase) does. Keep up to date on new ‘features’ that vendors try to sneak into your devices (like the aforementioned Amazon Sidewalk) and disable them when required.

Finally, turn off, disconnect (or simply don’t buy) anything that you don’t absolutely need. This means old ‘skills’ in Alexa. This means unnecessary connections to other Smart Devices. Maybe this means disabling all of Alexa’s purchase capabilities entirely. And, speaking of devices, do you really need your pressure cooker to be on the internet? (The answer can be ‘yes’ … different people have different culinary needs. I’m just saying, you know… think about it.)

Remember, the general tradeoff is between security and convenience- there’s a balance that’s right for you. Figure out what that balance is, and configure your environment (and the devices you choose to allow into your environment) unyieldingly against that balance.

Bonus Random Information About Roomba

Barely related side note that I found entirely by accident while researching this article: Roomba actually has a very active hacking subculture around changing the behavior of their robots. iRobot is fine with this, and has been for over a decade. They even provide a line of strictly educational robots called Create (see here for a detailed landing page) that use the identical “Roomba Open Interface,” allowing users to “manipulate Roomba’s behavior and read its sensors through a series of commands […] by way of a PC or microcontroller that is connected to the Mini-DIN connector external hardware communication.” iRobot has also permitted professional roboticists as well as enthusiasts to take this even further. Did you ever want to turn your Roomba into a printer? Or use it to play basketball? The community has you covered.

This side note is important because it highlights that even a very active and invested company like iRobot has to fight a constant battle against bad actors. And it appears that they have been successful, with a good history of security updates and a robust data protection policy. Other products in the space, however, are not so safe. There have been reports of automated vacuums that can be turned into remote spying devices through cameras or LiDAR for years now.